Celebrating Madonna’s Psychedelic Masterwork

Rob Sheffield at RollingStone.com joins the Ray of Light celebrations discussion how Madonna, inspired by motherhood and yoga, reinvented herself on her most passionate album to date.

Happy birthday to Ray of Light, the masterwork that introduced the world to Cosmic Psychedelic Madonna, 20 years ago this week. Ray of Light was the queen’s first proper album in four years, dropping on March 3rd, 1998, a week after she unveiled her new sound with the single Frozen. It was Madonna’s motherhood album, after giving birth to daughter Lourdes. It was her avant-techno move, with U.K. producer William Orbit. It was her spiritual-awakening statement. But Ray of Light holds up as her most soulful and passionate music ever – a libido-crazed disco-hippie mom pushing 40 and proud of it, flaunting her artiest emotional extremes. As Ray of Light boomed out of radios all year, with Madonna chanting her mantra – “And I feeeel! And I feeeel!” – she seemed to be feeling twice as hard as everyone else.

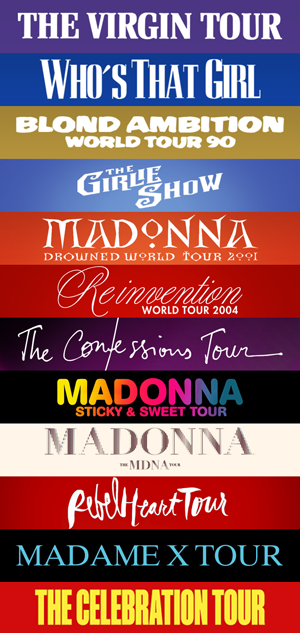

By all rights, Ray of Light should have been a pretentious disaster. Yet it turned out to be a new peak, setting Ms. Ciccone off on a glorious four-year run: the 1999 single Beautiful Stranger, the 2000 album Music, the 2001 Drowned World Tour. If you’re the kind of fan who reveres her as a musician first, not a celebrity, this was the hot streak of her life. You could compare it to Elvis Presley’s mature phase with the ’68 Comeback Special and From Elvis in Memphis. Except at 42, Elvis was dead, while Madonna was just gearing up for her next phase, where she discovered Kabbalah, converted to Judaism and started asking people to call her “Esther.” Never say she isn’t ecumenical.

Ray of Light is easily the most intense pop album ever made by a 39-year-old – Madonna spends these songs celebrating her newborn daughter, mourning her long-lost mother and reckoning with her messed-up adult self. She also contemplates her newfound Lilith Fair–era consciousness, going off about karma and yoga. As she explained in Billboard, “I feel like I’ve been enlightened, and that it’s my responsibility to share what I’ve learned so far with the world.” Ominous words from any pop star, let alone this one. But she made it feel mighty real. (Like another album we all loved in 1998: Hello Nasty, a spiritual manifesto from the opening act on her first tour, the Beastie Boys.) Even those of us who’d devoted our lives to worshipping Madonna weren’t prepared for an album this great.

Strange as it seems now, people back then were mildly obsessive about the idea of Madonna being “over.” Predicting the end of her career was a weirdly popular Nineties fad, like swing dancing or psychic hotlines. The semi-monthly “is she finally done?” debate kicked up every time she did something ridiculous, which she did all the damn time, from her poetic musings in the Sex book (“My pussy is the temple of learning”) to her erotic thriller Body of Evidence, where she played a serial killer who specialized in humping men to death. The U.K. music mag Melody Maker, for its 1992 year-in-review issue, polled experts on the year’s big question: Has Madonna turned into a pathetic exhibitionist? The wisest answer came from (of all people) Right Said Fred’s lead singer: “Being an exhibitionist is only pathetic when nobody’s watching you.”

The queen kept expanding her sound – the Babyface collabo Take a Bow spent seven weeks at Number One in 1995. She also did vocal training for the Evita soundtrack. (Count me among the fans who thinks Babyface taught her a hell of a lot more about singing than Andrew Lloyd Webber did.) But it was still considered exotic to take Madonna seriously for her music, rather than her image. It took Ray of Light to change that.

Her producer William Orbit had just worked wonders with U.K. ingenue Beth Orton, on her classic folkie-techno debut Trailer Park. Madonna playfully renamed herself “Veronica Electronica,” throwing in lots of what she and Orbit called “teenage-angst guitars.” They set the tone in the opening ballad, an emotional powerhouse called Drowned World/Substitute for Love. There’s too many gimmicks in the mix: moody electro bleeps, wind chimes, sitar, drum ‘n’ bass snare rattles, Sixties string samples, a very 1998-sounding vibraphone. Yet it never feels crowded or contrived – Madonna gives herself room to breathe deep, as she sings about letting go of the past and moving on. She keeps looping back to a mantra from John Lennon: “Now I find I’ve changed my mind.” (The Beatles’ “Help,” where John confessed his adult despair, was the perfect song to echo here.) When the rock guitar kicks in, at the three-minute point, it hits like a moment of pure serenity.

Read the full story on RollingStone.com.